Written by: Dave Smith

DSD Co-Founder

This article is pulled from the original publisher Breakthrough Magazine. To see the original version of this article, Click Here.

On November 20th, 2012, out of the blue, a panic came over me. Over the prior few weeks I had been wondering what my mentor of 28 years, legend fish artist Ron Pittard of Seaside, Oregon, had been up to and how he was doing, but hadn’t heard from him in a couple months. Now, all of the sudden I had the strong sense that something was terribly wrong. I immediately sent emails and Facebook messages to several of the Pittard family members, telling them that I had never gone this long without hearing from Ron. Ron’s daughter Mary replied almost immediately with news that realized my worst fears: “Hi Dave, we were just talking about you today. Dad is in St. Vincent in a hospice bed. He had a bleeding ulcer which caused a heart attack. Just a matter of days left. He wanted me to contact you about some of the things in his shop that he thought you could use.”

I just got weak and started sobbing, but thankfully, my wonderful wife and daughter snapped to action and rushed me to the hospital to have one final conversation with the one person who had more of an impact on my artistic and professional career than any other. When we arrived he grabbed my hand and squeezed it tight and said, “The end of a chapter…” I thanked him for a lifetime of mentoring and told him he was my greatest inspiration. In his usual kind and gracious way, he told me “I could say the same about you,” and at that point my battle to fight off a river of tears was lost. I was a wreck!

We all wish for a last chance to say what we’d like to say to a loved one, but when it comes down to actually going through with it, it’s excruciatingly sad. Still, I was thankful for the opportunity and promised him I would keep his legacy alive.

I first met Ron Pittard in the summer of 1983. I was 20 years old and at a juncture in my taxidermy career. Although I enjoyed all facets of taxidermy, I felt to really excel I would need to pick one area and focus on it. The choice really came down to birds or fish—I loved both. The Northwest already was blessed with such bird taxidermy greats as Rip Caswell, Dan Smith, and Stefan Savides, and little did we know at the time that we would be further endowed with up-and-comers Mike Vernelson and Patrick Bradburn. Plus, to be honest, I wasn’t sure I had the special kind of patience it takes to become a really good bird taxidermist.

It was around that time that I kept hearing about the “legend” of Ron Pittard. I was told that there was an artist in Seaside, Oregon, that makes easily the best fish on earth, and that he is so sought after that his location was a closely held secret, and that one of the prerequisites of him taking on your fish was that you would tell no one of his location! I was intrigued to say the least. Every fish taxidermist I knew was struggling to stay busy and spending a lot of money on marketing, yet here was a guy with no phone and no advertising, charging far more than anyone else, and was trying to stay hidden because he had more work than he could handle.

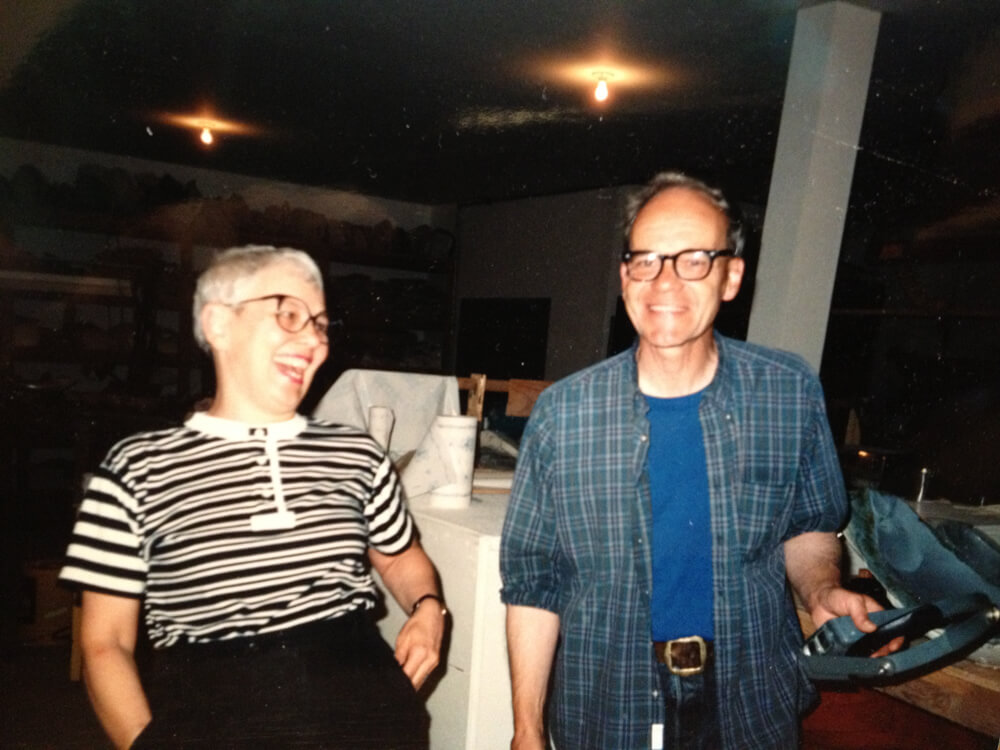

Without a clue of how to find him, one day I got a little tidbit of information: that Ron’s wife, Suzanne, worked at the local library in Seaside. I’m not proud of what I did on that day, but I did it, and it’s done now. I lied through my teeth. I walked in and told her that I had a fish to bring to Ron and she gave me the top-secret directions. I was nervous as could be as I drove to his shop in a small industrial part of town. I knocked on the door a few times, and instead of opening the door, a large roll-up door began opening and there he stood in the flesh. This mythical creature seemed to be an ordinary man, but as I would learn over the next few hours as I bugged the heck out of him, there was nothing ordinary about him.

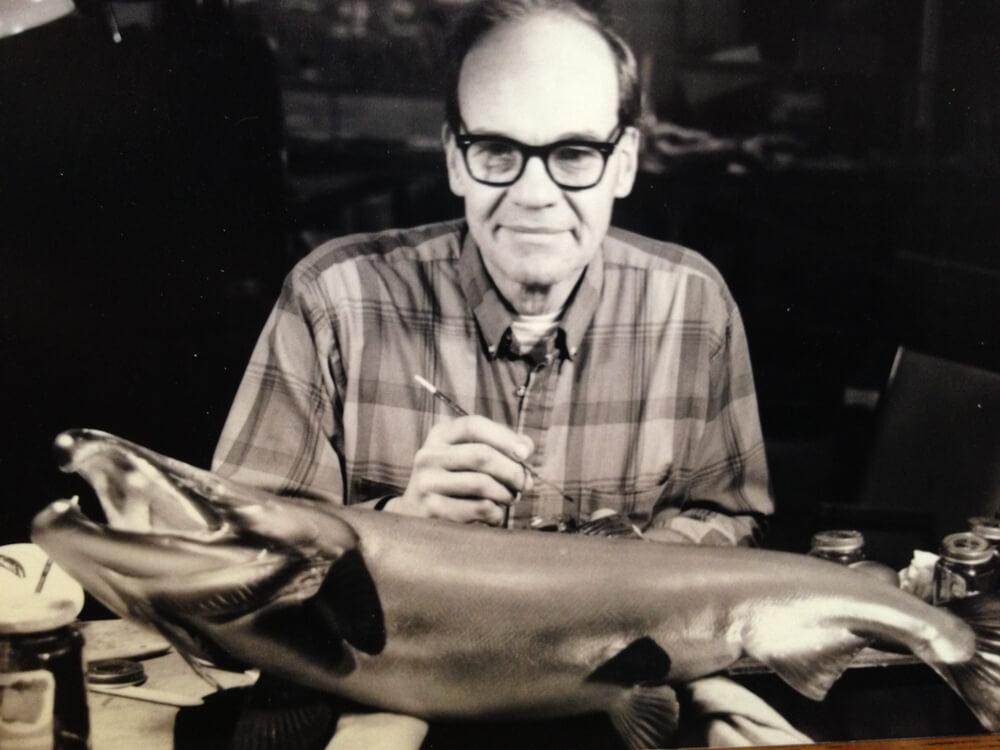

I tried to focus on introducing myself and explaining why and how I was there, but I was overwhelmed by what I saw. Long tables with fiberglass fish bodies all primed gray and ready to paint, like nothing I had ever seen before. Each fish was full and flawless with a complete inner mouth, in the most incredible, fishy, action poses. There was not a wrinkle or shrunken area and not a scale missing or blurred. The fins were flexible and transparent with great curves and the hand-carved gills looked like they were gorged with blood. I loved that they were super durable and would last forever.

As if that wasn’t enough, next I saw a group of finished fish, mostly cohos. His painting was even better than his molding and casting. His hand-made eyes were the fishiest looking I had ever seen, and were the first ever to be suspended in translucent resin when set. Each scale was individually and evenly painted—they glistened! Several of the oceanbright silvers had perfect little colonies of sea-lice off the tips of the pterygiophores. I loved the painted underwater scene backgrounds behind every fish, too.

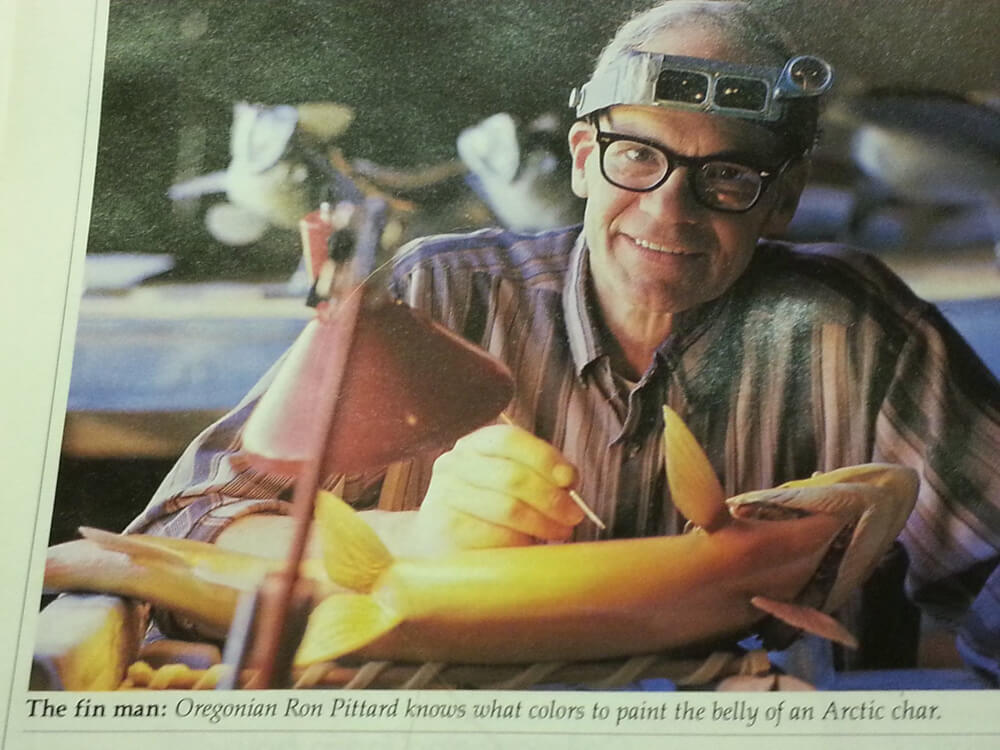

In 1979, Ron quit his electronics job to pursue his career as a fish artist. One of the first things he did as a “free man” was to enlist his services in the Columbia River Estuary Project. Working closely with biologists, Ron learned invaluable things about how fish and marine life work and what they look like, right down to the cellular level. This was a huge breakthrough in his success. Another valuable piece of advice he got from an accomplished portrait and landscape artist was to learn to paint a fish successfully in 2-D so mastering 3-D painting would become much easier. As Ron put it, “I could do better work if I understood the art involved.” His ability to paint 2-D fish became so good that he started rendering study charts of several different groups of fish and they sold very well.

As it was perfected, the Ron Pittard method consisted of molding fish in plaster, and then tooling the mold to remove any imperfections or add back any missing scales, etc. Being able to tool the mold meant that having a poor specimen to mold was inconsequential because any issue with the fish was fixable. It meant more work of course, but all fish could be equally flawless when finished. Ron would cast each fish model in two halves and then bind the halves together. This made for perfect seams, less wear and tear on the molds, and the ability to add in hand-carved gills, inner mouth, and support rods from the inside of the fish before the halves were joined together. It also enabled him to add curves to the fins and to make them as thin as he wanted because he could sand them down from the inside. Insisting that plaster was an “archaic” method, nearly everyone else had been trying to cast a whole fish with it, as they do to this day with every other molding and casting system besides plaster.

When it came to painting, Ron developed his approach based on his findings while working at the Columbia River Estuary Project. He surmised that most of the brilliance we see on real fish scales are the result of a bright, transparent chrome/silver, and that any scales that appear to be “gold,” for example, are gold because of yellow pigments refracting through that bright silver. Hence, he would spray on very light washes of transparent colors and clear coats, and then hand-paint an ultra-bright, in transparent silver on each scale over the color, then repeat the process and build up layer after layer to create true depth to the painting.

The silver he used was a lead-based paint that they stopped making in 1963. Ron had more than a lifetime supply of this special paint. Ron’s shop was broken into at one point; the thief wanted the priceless paint, among other things. It was said that when the perpetrator found out he still had to paint each scale several times to build up its brilliance, he lost all interest. Ron became the master at the use of that silver paint. He learned exactly what colors to spray early on to be able to spray certain other colors at the last stage to achieve the affect needed. On a rainbow trout, for example, you would swear that he hand-painted gold scales on the back, but Ron never did. Over time, his ability to paint a perfect scale shape with one, lightning quick stroke of a brush was amazing. He never outlined a scale first, and he never did any scale tipping, and he rarely ever rested his hand on the fish while painting. The beauty of the silver paint was that it did not show up as an opaque gray in areas that weren’t reflecting light. The bad news was that unlike the common opaque graybased silvers, you had to paint each scale several times to achieve this beauty. Ron was like a machine with it. He would put together a group of a dozen or so fish and then paint all the scales over the next several days with his light, transparent, sprayed washes in between scale coats until they were done.

Many of Ron’s fish called for spots or detailed patterns or markings. For these he hand-brushed them using artist’s oil paints. There were no compatibility issues because the colors he sprayed were from the same paint, just with lacquer and lacquer thinner added. He never used any conventional taxidermist’s supplies or paint and never used any commercially-available fish “blanks.”

Another unique, artistic touch that Ron became known for was his framed painting behind each fish, each of an underwater scene and each was unique to that fish. This method came partially out of necessity as Ron was constantly having to ship fish, and having the fish securely attached to a sturdy wooden backboard made crating and shipping easy. But the style made his work instantly recognizable and has been honored and respected to this day as his trademark style. Occasionally, a client would ask if he would do a bare fish with only a small hanger on the back and Ron would always refuse. He was pretty adamant about that and always made me promise to continue the tradition, which I gladly obliged.

Things really started rolling and Ron was outgrowing one shop after another. He finally got into a great shop, only to get the news that the landlord had been failing to pay taxes on it and if Ron wanted to stay, he would have to buy the building and pay the back taxes, which he reluctantly did. That turned out to be a huge blessing because shortly after that, a large commercial developer needed that property bad and was willing to pay enough to make it worth moving again and starting all over. I remember Ron showing my parents and me the blueprints of his new shop to be built on the Necanicum River with a large apartment above. It was Ron’s dream shop and it came to fruition.

All throughout the 1990’s and into the new millennium, Ron was living his dream of making fish replicas full time. He was making usually 60 to 80 fish per year; in a few years he would make over 90. He divided his time between fish replicas and painting his fish charts. His charts were selling very well, which supplemented his income. He also landed quite a few good jobs making large fish dioramas and displays for hatcheries, dams, and museums. In addition to this he did several technical drawings of marine invertebrates and miscellaneous odd jobs, usually related to marine life.

For the most part he successfully kept his location secret. Occasionally, one of his clients would enter one of his fish in a taxidermy competition, which Ron asked people not to do. There would always be a surge of new would-be clients searching for him soon after, or one of the local news crews tracking him down and asking him for a story, which Ron always gladly did.

Ron was such a talented artist and wanted time to explore new avenues. I felt like he had some art projects inside him that just had to get out. His lifetime of hard work had afforded him the ability to pursue these. He asked me to take on a client list of loyal, but persistent clients which, again, I was glad to do. Just when I thought I had seen the limit of Ron’s artistic ability, he was producing flat-art paintings that were jaw-dropping. Next, he did some incredible clay sculptures; he even made his own oilbased clay. He took time to really learn computers and mastered several art-based software programs. Then he got into power wood carving. These were usually very large, un-painted, freehand carvings. Some were of fish and lots of everything else, including Native American lore. When I had to cut down my giant maple tree in my front yard, Ron pleaded with me to find a way to get it to him, which of course I was glad to—I always loved the few times I could actually do something for him after all he had done for me.

As much as I loved being in his shop and visiting with Ron, I’ll admit that it wasn’t quite the same without groups of fiberglass fish going. Quite a few years went by with no fish as he had retired from fish replica work. I had been doing fish from his molds and from my own, but who wants to see his own work? Then, shortly after Dale Hert, my best friend of 32 years, passed away, I went to visit Ron and got a surprise: he was working on a new group of fiberglass fish! I felt like I had just lost a part of my life, but regained another that had previously been lost. I started a regimen of coming over once a week to help paint scales and see if we couldn’t get this group finished.

Sadly, it was not to be. I couldn’t keep up with going that often at that time of year because of my own work, and Ron was busy a lot of the time as his wife Suzy needed special care. He was an incredibly dedicated husband. Those would be the last fish that Ron Pittard ever worked on.

I went to Ron’s shop a couple weeks ago for the last time and picked up those fish and vowed to finish them. Closing the door and turning the lights off in that shop was one of the most painful things I ever did. I had to remind myself of what Ron once told me. He had collapsed on his deck one year and thought he was going to die and it was only by chance that he got discovered and taken to a hospital. He told me that as he lay there, sure these were his last moments on earth, all he could think about was how thankful he was to have lived on the estuary and to have been able to do his life’s work with the support of a great wife and family.

In my own life I have failed him. I could never work as hard as him and I always let distractions like fishing and hunting get in the way of continuing his legacy in a worthy way.

I ended up in the “bird business” after all, as I now make hunting decoys for a living and work on fish in my spare time. Although I’m sure Ron had hoped that I would stick with fish full time, in his usual kind and selfless ways he was always incredibly proud and supportive of me and my work. He was glad I was making a living related to wildlife art. I think he knew I would do more fish later in life. He would always insist that I had surpassed his abilities in fiberglass fish, which I can assure you is not true. As I looked through some of his old notebooks and photo albums, I was humbled to see that he had more pictures of fish I had done than I do myself. That was Ron—incredibly gracious and humble. One time my mom referred to him as “the best” in the business and he quickly corrected her, “Please, maybe ‘among’ the best.”

But this is not the end of the Ron Pittard story, not by a long shot. Me, I have his memory, his teachings, tons of his incredible molds, and of course the top-secret silver paint! There’s still time, but more importantly, so many of you have already been inspired by him and carry on his legacy. Ron started the hand-painted scale and custom molding revolution and it’s been spreading rapidly. Look at the effect he has already had on guys like Dave Campbell, Jeff Lumsden, Pete Harum, Rick Krane, and Luke Filmer, just to name a few! Let’s all continue keeping his legacy alive.

When asked about his life’s work, Ron once described it as “fascinating and a challenge, and to get done, I have to hide from everybody.” Now, for the first time, we all know where Ron Pittard’s glorious shop is, and we’ll see him there in time.